“There are here,” said he, “three distinct documents, probably three copies of the same missive, translated into three different languages: one English, another French, and the third German. The few words that remain leave no doubt on this point.”

“But these words have at least a meaning?” said Lady Glenarvan.

“That is difficult to say, my dear Helena. The words traced on these papers are very imperfect.”

“Perhaps they will complete each other,” said the major.

“That may be,” replied Captain Mangles. “It is not probable that the water has obliterated these lines in exactly the same places on each, and by comparing these remains of phrases we shall arrive at some intelligible meaning.”

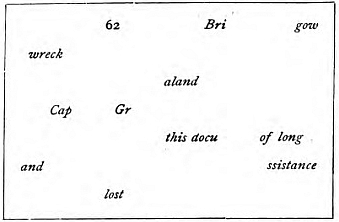

“We will do so,” said Lord Glenarvan; “but let us proceed systematically. And, first, here is the English document.”

It showed the following arrangement of lines and words:

“That does not mean much,” said the major, with an air of disappointment.

“Whatever it may mean,” replied the captain, “it is good English.”

“There is no doubt of that,” said his lordship. “The words wreck, aland, this, and, lost, are perfect. Cap. evidently means captain, referring to the captain of a shipwrecked vessel.”

“Let us add,” said the captain, “the portions of the words docu. and ssistance, the meaning of which is plain.”

“Well, something is gained already!” added Lady Helena.

“Unfortunately,” replied the major, “entire lines are wanting. How can we find the name of the lost vessel, or the place of shipwreck?”

“We shall find them,” said Lord Edward.

“Very likely,” answered the major, who was invariably of the opinion of every one else; “but how?”

“By comparing one document with another.”

“Let us see!” cried Lady Helena.

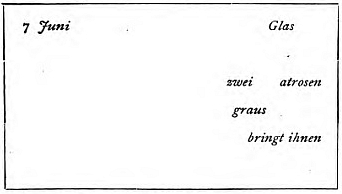

The second piece of paper, more damaged than the former, exhibited only isolated words, arranged thus:

“This is written in German,” said Captain Mangles, when he had cast his eyes upon it.

“And do you know that language?” asked Glenarvan.

“Perfectly, your lordship.”

“Well, tell us what these few words mean.”

The captain examined the document closely, and expressed himself as follows:

“First, the date of the event is determined. 7 Juni. means June 7th, and by comparing this figure with the figures ‘62,’ furnished by the English document, we have the date complete,—June 7th, 1862.”

“Very well!” exclaimed Lady Helena. “Go on.”

“On the same line,” continued the young captain, “I find the word Glas, which, united with the word gow. of the first document, gives Glasgow. It is plainly a ship from the port of Glasgow.”

“That was my opinion,” said the major.

“The second line is missing entirely,” continued Captain Mangles; “but on the third I meet with two important words zwei, which means two, and atrosen, or rather matrosen, which signifies sailors. in German.”

“There were a captain and two sailors, then?” said Lady Helena.

“Probably,” replied her husband.

“I will confess, your lordship,” said the captain, “that the next word, graus, puzzles me. I do not know how to translate it. Perhaps the third document will enable us to understand it. As to the two last words, they are easily explained. Bringt ihnen. means bring to them, and if we compare these with the English word, which is likewise on the sixth line of the first document (I mean the word assistance), we shall have the phrase bring them assistance.”

“Yes, bring them assistance,” said Glenarvan. “But where are the unfortunates? We have not yet a single indication of the place, and the scene of the catastrophe is absolutely unknown.”

“Let us hope that the French document will be more explicit,” said Lady Helena.

“Let us look at it, then,” replied Glenarvan; “and, as we all know this language, our examination will be more easy.”

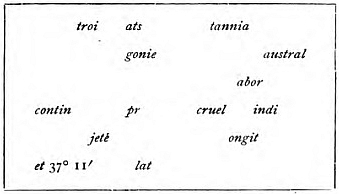

Here is an exact fac-simile of the third document:

“There are figures!” cried Lady Helena. “Look, gentlemen, look!”

“Let us proceed in order,” said Lord Glenarvan, “and start at the beginning. Permit me to point out one by one these scattered and incomplete words. I see from the first letters troi. ats. (trois-mats), that it is a brig, the name of which, thanks to the English and French documents, is entirely preserved: The Britannia. Of the two following words, gonie. and austral, only the last has an intelligible meaning.”

“That is an important point,” replied Captain Mangles; “the shipwreck took place in the southern hemisphere.”

“That is indefinite,” said the major.

“I will continue,” resumed Glenarvan. “The word abor. is the trace of the verb aborder. (to land). These unfortunates have landed somewhere. But where? Contin!. Is it on a continent? Cruel!”

“’Cruel!’” cried Mangles; “that explains the German word graus, grausam, cruel!”

“Go on, go on!” cried Glenarvan, whose interest was greatly excited as the meaning of these incomplete words was elucidated. “Indi! Is it India, then, where these sailors have been cast? What is the meaning of the word ongit? Ha, longitude! And here is the latitude, 37° 11’. In short, we have a definite indication.”

“But the longitude is wanting,” said MacNabb.

“We cannot have everything, my dear major,” replied Glenarvan; “and an exact degree of latitude is something. This French document is decidedly the most complete of the three. Each of them was evidently a literal translation of the others, for they all convey the same information. We must, therefore, unite and translate them into one language, and seek their most probable meaning, the one that is most logical and explicit.”

“Shall we make this translation in French, English, or German?” asked the major.

“In English,” answered Glenarvan, “since that is our own language.”

“Your lordship is right,” said Captain Mangles, “besides, it was also theirs.”

“It is agreed, then. I will write this document, uniting these parts of words and fragments of phrases, leaving the gaps that separate them, and filling up those the meaning of which is not ambiguous. Then we will compare them and form an opinion.”

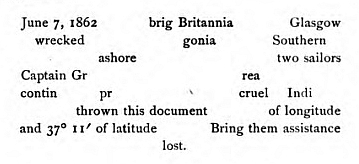

Glenarvan at once took a pen, and, in a few moments, presented to his friends a paper on which were written the following lines:

At this moment a sailor informed the captain that the Duncan was entering the Firth of Clyde, and asked his orders.

“What are your lordship’s wishes?” said the captain, addressing Lord Glenarvan.

“Reach Dumbarton as quickly as possible, captain. Then, while Lady Helena returns to Malcolm Castle, I will go to London and submit this document to the authorities.”

The captain gave his orders in pursuance of this, and the mate executed them.

“Now, my friends,” said Glenarvan, “we will continue our investigations. We are on the track of a great catastrophe. The lives of several men depend upon our sagacity. Let us use therefore all our ingenuity to divine the secret of this enigma.”

“We are ready, my dear Edward,” replied Lady Helena.

“First of all,” continued Glenarvan, “we must consider three distinct points in this document. First, what is known; second, what can be conjectured; and third, what is unknown. What do we know? That on the 7th of June, 1862, a brig, the Britannia, of Glasgow, was wrecked; that two sailors and the captain threw this document into the sea in latitude 37° 11’, and in it ask for assistance.”

“Exactly,” replied the major.

“What can we conjecture?” resumed Glenarvan. “First, that the shipwreck took place in the South Seas; and now I call your attention to the word gonia. Does it not indicate the name of the country which they reached?”

“Patagonia!” cried Lady Helena.

“Probably.”

“But is Patagonia crossed by the thirty-seventh parallel?” asked the major.

“That is easily seen,” said the captain, taking out a map of South America. “It is so: Patagonia is bisected by the thirty-seventh parallel, which crosses Araucania, over the Pampas, north of Patagonia, and is lost in the Atlantic.”

“Well, let us continue our conjectures. The two sailors and the captain abor, land. Where? Contin,—the continent, you understand; a continent, not an island. What becomes of them? We have fortunately two letters, pr, which inform us of their fate. These unfortunates, in short, are captured. (pris) or prisoners. By whom? The cruel Indians. Are you convinced? Do not the words fit naturally into the vacant places? Does not the document grow clear to your eyes? Does not light break in upon your mind?”

Glenarvan spoke with conviction. His looks betokened an absolute confidence; and his enthusiasm was communicated to his hearers. Like him they cried, “It is plain! it is plain!”

A moment after Lord Edward resumed, in these terms:

“All these hypotheses, my friends, seem to me extremely plausible. In my opinion, the catastrophe took place on the shores of Patagonia. However, I will inquire at Glasgow what was the destination of the Britannia, and we shall know whether she could have been led to these regions.”

“We do not need to go so far,” replied the captain; “I have here the shipping news of the Mercantile and Shipping Gazette, which will give us definite information.”

“Let us see! let us see!” said Lady Glenarvan.

Captain Mangles took a file of papers of the year 1862, and began to turn over the leaves rapidly. His search was soon ended; as he said, in a tone of satisfaction,—

“May 30, 1862, Callao, Peru, Britannia, Captain Grant, bound for Glasgow.”

“Grant!” exclaimed Lord Glenarvan; “that hardy Scotchman who wished to found a new Scotland in the waters of the Pacific?”

“Yes,” answered the captain, “the very same, who, in 1861, embarked in the Britannia at Glasgow, and of whom nothing has since been heard.”

“Exactly! exactly!” said Glenarvan; “it is indeed he. The Britannia left Callao the 30th of May, and on the 7th of June, eight days after her departure, she was lost on the shores of Patagonia. This is the whole story elucidated from the remains of these words that seemed undecipherable. You see, my friends, that what we can conjecture is very important. As to what we do not know, this is reduced to one item, the missing degree of longitude.”

“It is of no account,” added Captain Mangles, “since the country is known; and with the latitude alone, I will undertake to go straight to the scene of the shipwreck.”

“We know all, then?” said Lady Glenarvan.

“All, my dear Helena: and these blanks that the sea has made between the words of the document, I can as easily fill out as though I were writing at the dictation of Captain Grant.”

Accordingly Lord Glenarvan took the pen again, and wrote, without hesitation, the following note:

|

“June 7, 1862.—The brig Britannia of Glasgow was wrecked on the shores of Patagonia, in the Southern Hemisphere. Directing their course to land, two sailors and Captain Grant attempted to reach the continent, where they will be prisoners of the cruel Indians. They have thrown this document into the sea, at longitude——, latitude 37° 11’. Bring them assistance or they are lost.” |

“Good! good! my dear Edward!” said Lady Glenarvan; “and if these unfortunates see their native country again, they will owe this happiness to you.”

“And they shall see it again,” replied Glenarvan. “This document is too explicit, too clear, too certain, for Englishmen to hesitate. What has been done for Sir John Franklin, and so many others, will also be done for the shipwrecked of the Britannia.”

“But these unfortunates,” answered Lady Helena, “have, without doubt, a family that mourns their loss. Perhaps this poor Captain Grant has a wife, children——”

“You are right, my dear lady; and I charge myself with informing them that all hope is not yet lost. And now, my friends, let us go on deck, for we must be approaching the harbor.”

Indeed, the Duncan had forced on steam, and was now skirting the shores of Bute Island. Rothesay, with its charming little village nestling in its fertile valley, was left on the starboard, and the vessel entered the narrow inlets of the frith, passed Greenock, and, at six in the evening, was anchored at the foot of the basaltic rocks of Dumbarton, crowned by the celebrated castle.

Here a coach was waiting to take Lady Helena and Major MacNabb back to Malcolm Castle. Lord Glenarvan, after embracing his young wife, hurried to take the express train for Glasgow. But before going, he confided an important message to a more rapid agent, and a few moments after the electric telegraph conveyed to the Times and Morning Chronicle an advertisement in the following terms:

|

“For any information concerning the brig Britannia of Glasgow, Captain Grant, address Lord Glenarvan, Malcolm Castle, Luss, County of Dumbarton, Scotland.” |