FROM DIARY:

NOVEMBER 1—noon. A fine day, a brilliant sun. Warm in the sun, cold in the shade—an icy breeze blowing out of the south. A solemn long swell rolling up northward. It comes from the South Pole, with nothing in the way to obstruct its march and tone its energy down. I have read somewhere that an acute observer among the early explorers—Cook? or Tasman?—accepted this majestic swell as trustworthy circumstantial evidence that no important land lay to the southward, and so did not waste time on a useless quest in that direction, but changed his course and went searching elsewhere.

Afternoon. Passing between Tasmania (formerly Van Diemen’s Land) and neighboring islands—islands whence the poor exiled Tasmanian savages used to gaze at their lost homeland and cry; and die of broken hearts. How glad I am that all these native races are dead and gone, or nearly so. The work was mercifully swift and horrible in some portions of Australia. As far as Tasmania is concerned, the extermination was complete: not a native is left. It was a strife of years, and decades of years. The Whites and the Blacks hunted each other, ambushed each other, butchered each other. The Blacks were not numerous. But they were wary, alert, cunning, and they knew their country well. They lasted a long time, few as they were, and inflicted much slaughter upon the Whites.

The Government wanted to save the Blacks from ultimate extermination, if possible. One of its schemes was to capture them and coop them up, on a neighboring island, under guard. Bodies of Whites volunteered for the hunt, for the pay was good—£5 for each Black captured and delivered, but the success achieved was not very satisfactory. The Black was naked, and his body was greased. It was hard to get a grip on him that would hold. The Whites moved about in armed bodies, and surprised little families of natives, and did make captures; but it was suspected that in these surprises half a dozen natives were killed to one caught—and that was not what the Government desired.

Another scheme was to drive the natives into a corner of the island and fence them in by a cordon of men placed in line across the country; but the natives managed to slip through, constantly, and continue their murders and arsons.

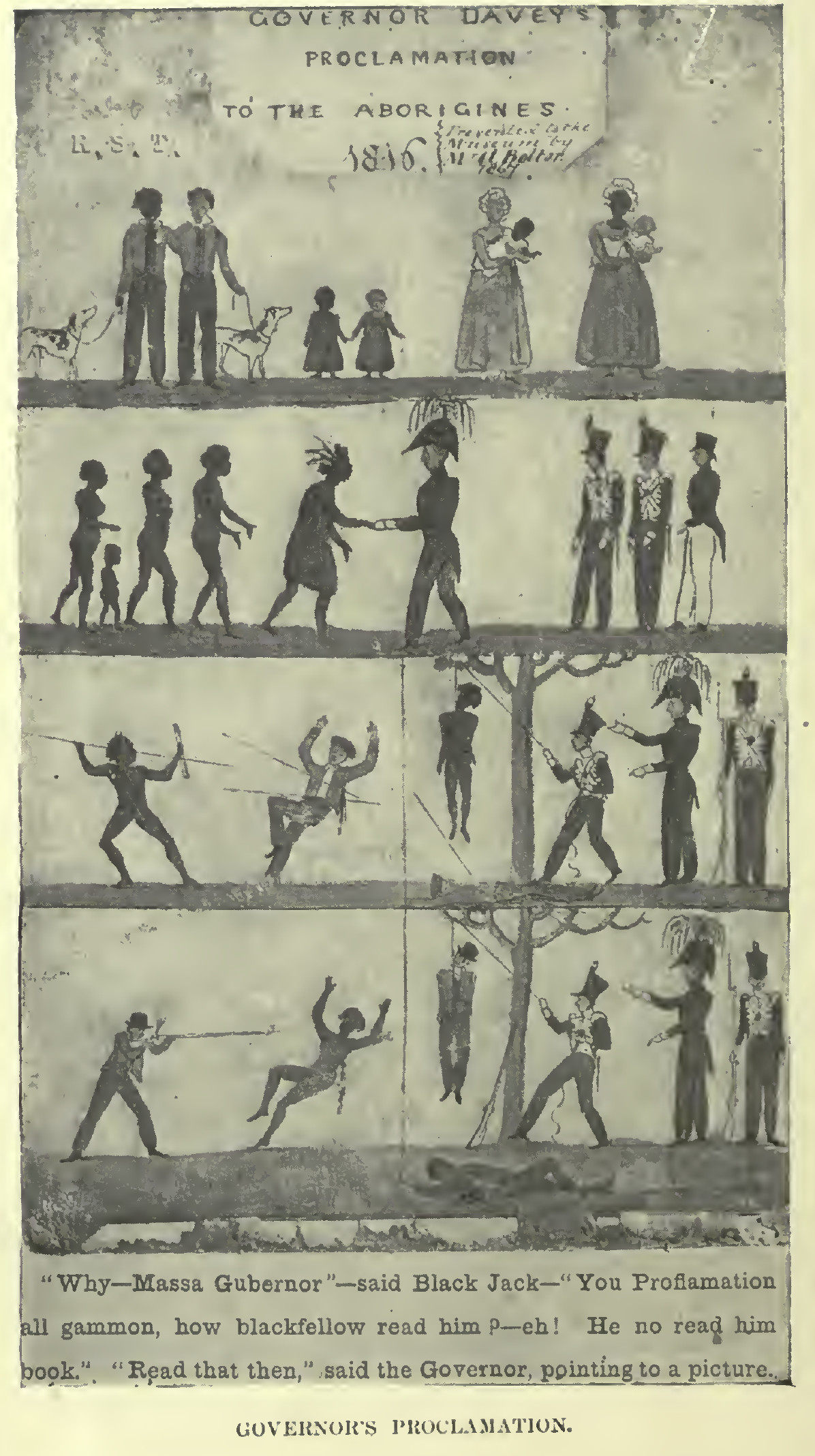

The governor warned these unlettered savages by printed proclamation that they must stay in the desolate region officially appointed for them! The proclamation was a dead letter; the savages could not read it. Afterward a picture-proclamation was issued. It was painted up on boards, and these were nailed to trees in the forest. Herewith is a photographic reproduction of this fashion-plate. Substantially it means:

|

1. The Governor wishes the Whites and the Blacks to love each other; 2. He loves his black subjects; 3. Blacks who kill Whites will be hanged; 4. Whites who kill Blacks will be hanged. |

Upon its several schemes the Government spent £30,000 and employed the labors and ingenuities of several thousand Whites for a long time with failure as a result. Then, at last, a quarter of a century after the beginning of the troubles between the two races, the right man was found. No, he found himself. This was George Augustus Robinson, called in history “The Conciliator.” He was not educated, and not conspicuous in any way. He was a working bricklayer, in Hobart Town. But he must have been an amazing personality; a man worth traveling far to see. It may be his counterpart appears in history, but I do not know where to look for it.

He set himself this incredible task: to go out into the wilderness, the jungle, and the mountain-retreats where the hunted and implacable savages were hidden, and appear among them unarmed, speak the language of love and of kindness to them, and persuade them to forsake their homes and the wild free life that was so dear to them, and go with him and surrender to the hated Whites and live under their watch and ward, and upon their charity the rest of their lives! On its face it was the dream of a madman.

In the beginning, his moral-suasion project was sarcastically dubbed the sugar-plum speculation. If the scheme was striking, and new to the world’s experience, the situation was not less so. It was this. The White population numbered 40,000 in 1831; the Black population numbered three hundred. Not 300 warriors, but 300 men, women, and children. The Whites were armed with guns, the Blacks with clubs and spears. The Whites had fought the Blacks for a quarter of a century, and had tried every thinkable way to capture, kill, or subdue them; and could not do it. If white men of any race could have done it, these would have accomplished it. But every scheme had failed, the splendid 300, the matchless 300 were unconquered, and manifestly unconquerable. They would not yield, they would listen to no terms, they would fight to the bitter end. Yet they had no poet to keep up their heart, and sing the marvel of their magnificent patriotism.

At the end of five-and-twenty years of hard fighting, the surviving 300 naked patriots were still defiant, still persistent, still efficacious with their rude weapons, and the Governor and the 40,000 knew not which way to turn, nor what to do.

Then the Bricklayer—that wonderful man—proposed to go out into the wilderness, with no weapon but his tongue, and no protection but his honest eye and his humane heart; and track those embittered savages to their lairs in the gloomy forests and among the mountain snows. Naturally, he was considered a crank. But he was not quite that. In fact, he was a good way short of that. He was building upon his long and intimate knowledge of the native character. The deriders of his project were right—from their standpoint—for they believed the natives to be mere wild beasts; and Robinson was right, from his standpoint—for he believed the natives to be human beings. The truth did really lie between the two. The event proved that Robinson’s judgment was soundest; but about once a month for four years the event came near to giving the verdict to the deriders, for about that frequently Robinson barely escaped falling under the native spears.

But history shows that he had a thinking head, and was not a mere wild sentimentalist. For instance, he wanted the war parties called in before he started unarmed upon his mission of peace. He wanted the best chance of success—not a half-chance. And he was very willing to have help; and so, high rewards were advertised, for any who would go unarmed with him. This opportunity was declined. Robinson persuaded some tamed natives of both sexes to go with him—a strong evidence of his persuasive powers, for those natives well knew that their destruction would be almost certain. As it turned out, they had to face death over and over again.

Robinson and his little party had a difficult undertaking upon their hands. They could not ride off, horseback, comfortably into the woods and call Leonidas and his 300 together for a talk and a treaty the following day; for the wild men were not in a body; they were scattered, immense distances apart, over regions so desolate that even the birds could not make a living with the chances offered—scattered in groups of twenty, a dozen, half a dozen, even in groups of three. And the mission must go on foot. Mr. Bonwick furnishes a description of those horrible regions, whereby it will be seen that even fugitive gangs of the hardiest and choicest human devils the world has seen—the convicts set apart to people the “Hell of Macquarrie Harbor Station”—were never able, but once, to survive the horrors of a march through them, but starving and struggling, and fainting and failing, ate each other, and died:

|

“Onward, still onward, was the order of the indomitable Robinson. No one ignorant of the western country of Tasmania can form a correct idea of the traveling difficulties. While I was resident in Hobart Town, the Governor, Sir John Franklin, and his lady, undertook the western journey to Macquarrie Harbor, and suffered terribly. One man who assisted to carry her ladyship through the swamps, gave me his bitter experience of its miseries. Several were disabled for life. No wonder that but one party, escaping from Macquarrie Harbor convict settlement, arrived at the civilized region in safety. Men perished in the scrub, were lost in snow, or were devoured by their companions. This was the territory traversed by Mr. Robinson and his Black guides. All honor to his intrepidity, and their wonderful fidelity! When they had, in the depth of winter, to cross deep and rapid rivers, pass among mountains six thousand feet high, pierce dangerous thickets, and find food in a country forsaken even by birds, we can realize their hardships. “After a frightful journey by Cradle Mountain, and over the lofty plateau of Middlesex Plains, the travelers experienced unwonted misery, and the circumstances called forth the best qualities of the noble little band. Mr. Robinson wrote afterwards to Mr. Secretary Burnett some details of this passage of horrors. In that letter, of Oct 2, 1834, he states that his Natives were very reluctant to go over the dreadful mountain passes; that ‘for seven successive days we continued traveling over one solid body of snow;’ that ‘the snows were of incredible depth;’ that ‘the Natives were frequently up to their middle in snow.’ But still the ill-clad, ill-fed, diseased, and way-worn men and women were sustained by the cheerful voice of their unconquerable friend, and responded most nobly to his call.” |

Mr. Bonwick says that Robinson’s friendly capture of the Big River tribe remember, it was a whole tribe—“was by far the grandest feature of the war, and the crowning glory of his efforts.” The word “war” was not well chosen, and is misleading. There was war still, but only the Blacks were conducting it—the Whites were holding off until Robinson could give his scheme a fair trial. I think that we are to understand that the friendly capture of that tribe was by far the most important thing, the highest in value, that happened during the whole thirty years of truceless hostilities; that it was a decisive thing, a peaceful Waterloo, the surrender of the native Napoleon and his dreaded forces, the happy ending of the long strife. For “that tribe was the terror of the colony,” its chief “the Black Douglas of Bush households.”

Robinson knew that these formidable people were lurking somewhere, in some remote corner of the hideous regions just described, and he and his unarmed little party started on a tedious and perilous hunt for them. At last, “there, under the shadows of the Frenchman’s Cap, whose grim cone rose five thousand feet in the uninhabited westward interior,” they were found. It was a serious moment. Robinson himself believed, for once, that his mission, successful until now, was to end here in failure, and that his own death-hour had struck.

The redoubtable chief stood in menacing attitude, with his eighteen-foot spear poised; his warriors stood massed at his back, armed for battle, their faces eloquent with their long-cherished loathing for white men. “They rattled their spears and shouted their war-cry.” Their women were back of them, laden with supplies of weapons, and keeping their 150 eager dogs quiet until the chief should give the signal to fall on.

“I think we shall soon be in the resurrection,” whispered a member of Robinson’s little party.

“I think we shall,” answered Robinson; then plucked up heart and began his persuasions—in the tribe’s own dialect, which surprised and pleased the chief. Presently there was an interruption by the chief:

“Who are you?”

“We are gentlemen.”

“Where are your guns?”

“We have none.”

The warrior was astonished.

“Where your little guns?” (pistols).

“We have none.”

A few minutes passed—in by-play—suspense—discussion among the tribesmen—Robinson’s tamed squaws ventured to cross the line and begin persuasions upon the wild squaws. Then the chief stepped back “to confer with the old women—the real arbiters of savage war.” Mr. Bonwick continues:

|

“As the fallen gladiator in the arena looks for the signal of life or death from the president of the amphitheatre, so waited our friends in anxious suspense while the conference continued. In a few minutes, before a word was uttered, the women of the tribe threw up their arms three times. This was the inviolable sign of peace! Down fell the spears. Forward, with a heavy sigh of relief, and upward glance of gratitude, came the friends of peace. The impulsive natives rushed forth with tears and cries, as each saw in the other’s rank a loved one of the past. “It was a jubilee of joy. A festival followed. And, while tears flowed at the recital of woe, a corrobory of pleasant laughter closed the eventful day.” |

In four years, without the spilling of a drop of blood, Robinson brought them all in, willing captives, and delivered them to the white governor, and ended the war which powder and bullets, and thousands of men to use them, had prosecuted without result since 1804.

Marsyas charming the wild beasts with his music—that is fable; but the miracle wrought by Robinson is fact. It is history—and authentic; and surely, there is nothing greater, nothing more reverence-compelling in the history of any country, ancient or modern.

And in memory of the greatest man Australasia ever developed or ever will develop, there is a stately monument to George Augustus Robinson, the Conciliator in—no, it is to another man, I forget his name.

However, Robertson’s own generation honored him, and in manifesting it honored themselves. The Government gave him a money-reward and a thousand acres of land; and the people held mass-meetings and praised him and emphasized their praise with a large subscription of money.

A good dramatic situation; but the curtain fell on another:

|

“When this desperate tribe was thus captured, there was much surprise to find that the £30,000 of a little earlier day had been spent, and the whole population of the colony placed under arms, in contention with an opposing force of sixteen men with wooden spears! Yet such was the fact. The celebrated Big River tribe, that had been raised by European fears to a host, consisted of sixteen men, nine women, and one child. With a knowledge of the mischief done by these few, their wonderful marches and their widespread aggressions, their enemies cannot deny to them the attributes of courage and military tact. A Wallace might harass a large army with a small and determined band; but the contending parties were at least equal in arms and civilization. The Zulus who fought us in Africa, the Maories in New Zealand, the Arabs in the Soudan, were far better provided with weapons, more advanced in the science of war, and considerably more numerous, than the naked Tasmanians. Governor Arthur rightly termed them a noble race.” |

These were indeed wonderful people, the natives. They ought not to have been wasted. They should have been crossed with the Whites. It would have improved the Whites and done the Natives no harm.

But the Natives were wasted, poor heroic wild creatures. They were gathered together in little settlements on neighboring islands, and paternally cared for by the Government, and instructed in religion, and deprived of tobacco, because the superintendent of the Sunday-school was not a smoker, and so considered smoking immoral.

The Natives were not used to clothes, and houses, and regular hours, and church, and school, and Sunday-school, and work, and the other misplaced persecutions of civilization, and they pined for their lost home and their wild free life. Too late they repented that they had traded that heaven for this hell. They sat homesick on their alien crags, and day by day gazed out through their tears over the sea with unappeasable longing toward the hazy bulk which was the specter of what had been their paradise; one by one their hearts broke and they died.

In a very few years nothing but a scant remnant remained alive. A handful lingered along into age. In 1864 the last man died, in 1876 the last woman died, and the Spartans of Australasia were extinct.

The Whites always mean well when they take human fish out of the ocean and try to make them dry and warm and happy and comfortable in a chicken coop; but the kindest-hearted white man can always be depended on to prove himself inadequate when he deals with savages. He cannot turn the situation around and imagine how he would like it to have a well-meaning savage transfer him from his house and his church and his clothes and his books and his choice food to a hideous wilderness of sand and rocks and snow, and ice and sleet and storm and blistering sun, with no shelter, no bed, no covering for his and his family’s naked bodies, and nothing to eat but snakes and grubs and offal. This would be a hell to him; and if he had any wisdom he would know that his own civilization is a hell to the savage—but he hasn’t any, and has never had any; and for lack of it he shut up those poor natives in the unimaginable perdition of his civilization, committing his crime with the very best intentions, and saw those poor creatures waste away under his tortures; and gazed at it, vaguely troubled and sorrowful, and wondered what could be the matter with them. One is almost betrayed into respecting those criminals, they were so sincerely kind, and tender, and humane; and well-meaning.

They didn’t know why those exiled savages faded away, and they did their honest best to reason it out. And one man, in a like case in New South Wales, did reason it out and arrive at a solution:

“It is from the wrath of God, which is revealed from heaven against cold ungodliness and unrighteousness of men.”

That settles it.